Is Forbidden Films a Hidden Treasure or Dumpster Fire?

DVD Distributed By: Kino Lorber / May 15, 2018

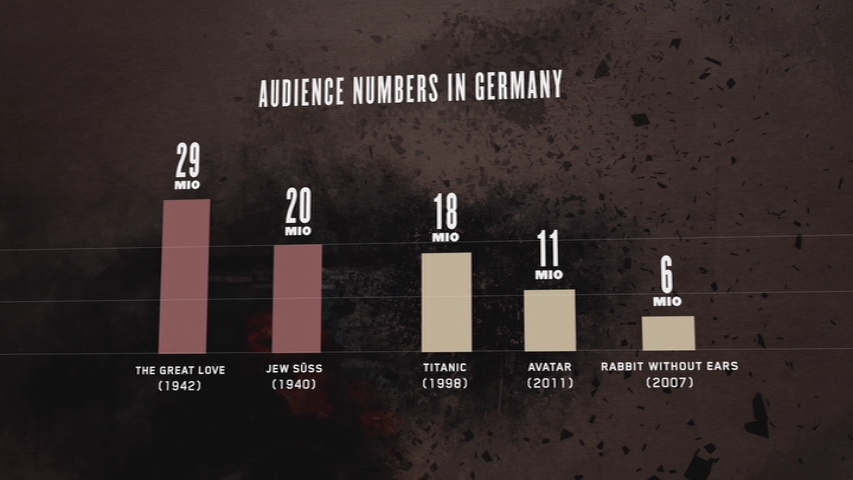

1,200 feature films were made in Germany’s Third Reich. According to experts, some 100 of these were blatant Nazi propaganda. Nearly seventy years after the end of the Nazi regime, more than 40 of these films remain under lock and key. Director Felix Moeller (Harlan: In the Shadow of Jew Süss) interviews German film historians, archivists and filmgoers in an investigation of the power, and potential danger, of cinema when used for ideological purposes. Utilizing clips from the films and recorded discussions from public screenings (permitted in Germany in educational contexts) in Munich, Berlin, Paris and Jerusalem, Moeller shows how contentious these 70-year-old films remain, and how propaganda can retain its punch when presented to audiences susceptible to manipulation.

Jimbo’s Take  (4 / 5)

(4 / 5)

Forbidden Films documents the people trying to answer one central question. Should Nazi propaganda films be released or remain banned? Unfortunately, this question fragments into about a hundred additional questions. Who should be the decision maker and gatekeeper of these films? If released, is there a moral obligation to explain or define the context of the films? And who defines the context or “truth” of these films?

Director Felix Moeller interviews critics, film scholars, former Neo-Nazi’s, and general movie goers in an effort to wrap his arms around this complex issue. The film explores the perspectives from interest groups representing the Jewish community, Polish community, film community, German community, etc. And you can imagine all of these view-points clashing in a battle of ideas and concerns.

Even you, the viewers, will come to the film with your own pre-conceived opinions on how these films should be handled. Should they be released? Banned? Burned? And the filmmakers challenge those pre-conceived notions nearly every step of the way.

The Third Reich produced roughly 1200 feature films and currently 40 Nazi propaganda films are literally under lock and key in Germany. One of these films is the Heimkehr (1941), translation “Homecoming”, about Maria Thomas (Paula Wessely) who is persecuted and eventually jailed by the “villainous” Polish townspeople.

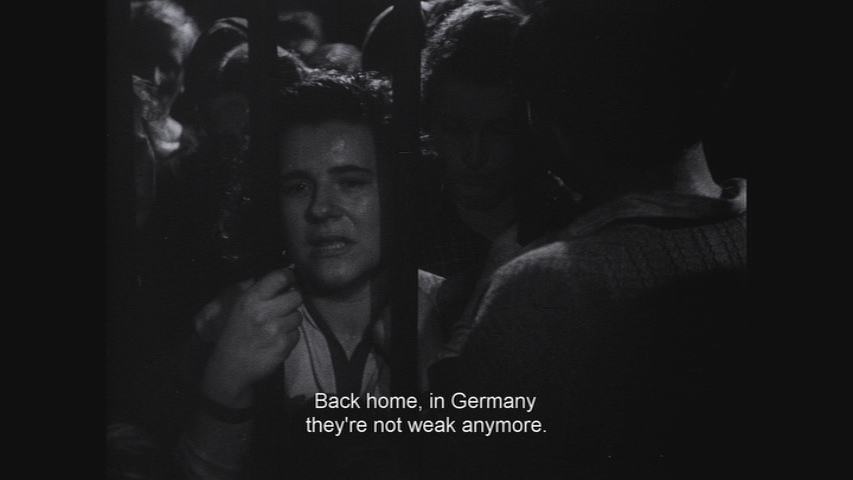

The documentary showcases several scenes from Heimkehr (1941). In one scene Maria, while jailed, gives an impassioned speech about the wonders of German life. She speaks of a better place where no one speaks Polish or Yiddish and where German’s can live peacefully. By the film’s end, Hitler’s army “saves” Maria and her captors, returning her to the homeland, and “liberating” the country of Poland.

The documentary showcases several scenes from Heimkehr (1941). In one scene Maria, while jailed, gives an impassioned speech about the wonders of German life. She speaks of a better place where no one speaks Polish or Yiddish and where German’s can live peacefully. By the film’s end, Hitler’s army “saves” Maria and her captors, returning her to the homeland, and “liberating” the country of Poland.

Heimkehr is propaganda designed to justify the Nazi invasion of Poland. But what’s most frightening is how completely effective and entertaining the film remains. The filmmakers capture an interview with one viewer who, in his observations, sides with the German protagonists. This gentleman even concludes that the film does a great job of showing how the Polish and British influence instigated the war, instead of the other way around.

And herein lies the dilemma. For the ill-informed, what is the truth? Who defines what information needs to supplement these films? If the films are released, do they get released “as is” and without explanation? Interviews with former Neo-Nazi’s may make you think otherwise. Two gentlemen formerly responsible for recruiting 13 and 14-year-olds explain how these movies can be easily used to skew opinions and perspectives of impressionable youth.

And herein lies the dilemma. For the ill-informed, what is the truth? Who defines what information needs to supplement these films? If the films are released, do they get released “as is” and without explanation? Interviews with former Neo-Nazi’s may make you think otherwise. Two gentlemen formerly responsible for recruiting 13 and 14-year-olds explain how these movies can be easily used to skew opinions and perspectives of impressionable youth.

What if each film was released with a historical expert to offer a counter point to each film? Jew Süss, which originally premiered at the Venice Film Festival in 1940, is considered to be one of the most dangerous and anti-Semitic Nazi propaganda films in existence. Many theater screenings are only conducted under stringent guidelines.

This documentary showcases a discussion between a film moderator, Sylvie Lindeperg, and an audience post Jew Süss screening. Many of the audience members seem shocked at how entertaining, well made, and effective Jew Süss remains today. One young man even states, “I think the ideas of this film are still out there.” Moderator Sylvie Lindeperg asks the audience if the film should be televised and the room almost universally agrees that it should not.

This documentary showcases a discussion between a film moderator, Sylvie Lindeperg, and an audience post Jew Süss screening. Many of the audience members seem shocked at how entertaining, well made, and effective Jew Süss remains today. One young man even states, “I think the ideas of this film are still out there.” Moderator Sylvie Lindeperg asks the audience if the film should be televised and the room almost universally agrees that it should not.

However, Moshe Zimmerman, Historian at Hebrew University, disagrees and believes TV audiences should see Jew Süss. Although, even he admits, “the viewer has to be a critical viewer.” The anti-Semitic message of Jew Süss isn’t front and center to the plot. It’s veiled in just a handful of well-timed lines of dialogue.

But how does one become a “critical viewer”? Do viewers need to be taught these skills early on? Zimmerman warns that you can’t “immunize someone against anti-Semitism with a lecture given before a screening of Jew Süss.”

But how does one become a “critical viewer”? Do viewers need to be taught these skills early on? Zimmerman warns that you can’t “immunize someone against anti-Semitism with a lecture given before a screening of Jew Süss.”

Forbidden Films then pivots and explores Germany’s attempt to de-Nazify many of the 1200 films of the Third Reich. Because many of these films were still high in demand and very popular after the war, a process was begun to cut and edit imagery and dialogue that was deemed offensive and dangerous. It could be the simple removal of the swastika or a line of dialogue about the Nazi war efforts.

The irony here is that this process flies against Germany’s own Censorship Ban of Art, 5. And the documentary speaks with many historians and scholars who are completely against the editing and re-imagining of German history, afraid this “cleaning up” does more harm than good. Didn’t America just go through a period of people removing certain statues and imagery just because they felt it was offensive?

The irony here is that this process flies against Germany’s own Censorship Ban of Art, 5. And the documentary speaks with many historians and scholars who are completely against the editing and re-imagining of German history, afraid this “cleaning up” does more harm than good. Didn’t America just go through a period of people removing certain statues and imagery just because they felt it was offensive?

There are many more topics explored in Forbidden Films that I won’t discuss here. Topics like the actors involved, Euthanasia, and the overall entertainment appeal of these films. Instead of exploring those topics here, I highly recommend that you search out this film for yourself.

Ultimately, Forbidden Films challenges all of us to listen with a critical ear, watch with a critical eye, and to be skeptical of the latent image. It also encourages discourse and debate. There are no immediate answers or quick solutions to be found within. But what makes Forbidden Films so captivating is the conflict of ideas, and the people in opposition to one another over 40 films. What makes it frightening are the parallels in today’s American media – TV, internet, print, social media.

Ultimately, Forbidden Films challenges all of us to listen with a critical ear, watch with a critical eye, and to be skeptical of the latent image. It also encourages discourse and debate. There are no immediate answers or quick solutions to be found within. But what makes Forbidden Films so captivating is the conflict of ideas, and the people in opposition to one another over 40 films. What makes it frightening are the parallels in today’s American media – TV, internet, print, social media.

Fighting over a small collection of films seems trivial on the surface, but I think the fight and discussion being brought to light by Forbidden Films is much broader and much more important. With any complex issue the more you understand, the more you discuss, the more your perspective may change. Are there cases where silencing, editing, and censoring is for the greater good? If so, how can we ever be certain that the truth may present itself?

Fighting over a small collection of films seems trivial on the surface, but I think the fight and discussion being brought to light by Forbidden Films is much broader and much more important. With any complex issue the more you understand, the more you discuss, the more your perspective may change. Are there cases where silencing, editing, and censoring is for the greater good? If so, how can we ever be certain that the truth may present itself?

Hidden Treasure/Dumpster Fire?

| Jimbo: |  (4 / 5) (4 / 5) |

| Average: |  (4 / 5) (4 / 5) |

[amazon_link asins=’B07BF25TBC’ template=’ProductCarousel’ store=’trashmenamaz-20′ marketplace=’US’ link_id=’095a35d7-666f-11e8-83b4-fd3356aefc0f’]

Special Features

- Original Theatrical Trailer